Self-Perceived Attitudes Toward End-of-Life Care among Nurses Working in Acute Hospital in Kenya

* Gladys Machira;

Irene G. Mageto;

James Mwaura;

-

* Gladys Machira: Department of Nursing Sciences, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

-

Irene G. Mageto: Department of Nursing Sciences, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

-

James Mwaura: Department of Nursing Sciences, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

-

May 07, 2020 |

-

Volume: 1 |

-

Issue: 1 |

-

Views: 4106 |

-

Downloads: 2781 |

Abstract

Background: Despite of the fact that nurses play a key role in caring for dying patients, nurses describe themselves as lacking confidence in providing care for the dying.

Aim: This study sought to assess nurses’ perceived attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care. Further, the study aimed to assess whether a relationship exists between work setting and nurses’ attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care.

Methods: Descriptive cross-sectional survey research design was utilized in this study. The data were collected from eight units in an acute hospital using a self-administrative questionnaire. A simple random sample consisted of 191 nurses and 173 nurses responded. Internal consistency among the questionnaire items was 0.94 Cronbach’s alpha (α).

Findings: The attitudes of Kenyan nurses toward caring for dying patients had deficiencies than the reported attitudes of nurses in other studies. A relationship was found between work setting and attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care. Most of the nurses who worked in the palliative care department (75%), and half of those who worked in the high dependence unit and oncology clinic reported favorable attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care. Majority of nurses reported that they had not received education on end-of-life nursing care.

Conclusion: The deficiencies in attitudes observed in this study may have occurred as a result of lack of education on end-of-life nursing care. The study highlights the need for development of end-of-life nursing care educational programmes in Kenya in both academic and clinical settings to facilitate nurses’ understanding of their attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care. This is especially so because attitudes are learned.

Abbreviations

EOL: End-of-Life; EOLC: End-of-Life Care; EOLNC: End-of-Life Nursing Care; HCPs: Health Care Professionals; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; NCDs: Non-Communicable Diseases.

Introduction

End-of-Life Care (EOLC) encompasses the support provided to the dying and their families and it incorporates all aspects of the care relating to dying, death and bereavement [1]. The most preferred place by people to die is hospital settings [2]. Globally, deaths are projected to rise from 55 million in 2016 to 75 million by 2040 and it was documented in literature that these deaths were accompanied by suffering that needs quality and compassionate EOLC [2,3]. Despite of the fact that nurses play a key role in caring for dying patients, nurses describe themselves as lacking confidence in providing care for the dying.

This was reported in a study that was conducted to explore the views of health care professionals (HCPs) as far as initiation of end-of-life (EOL) communication was concerned. The study noted that majority of nurses felt that initiating EOL discussions was mainly the role of the doctor [4]. They emphasized that their role was mainly supporting the patient (being the patient’s ear). That is, clarifying information provided by doctors to patients and their families while being supportive and comforting to patients as they internalize the bad news.

That notwithstanding, in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia among physicians and nurses, the nurses were noted to have significantly more positive attitudes towards advance directives [5]. Deficiencies in nurses’ attitudes toward EOLNC is documented in literature. For instance, inappropriate attitudes by nurses toward EOL care was reported in a study by McConnell, Scott, and Potter (2016). The study noted that the health care professionals (HCPs) among them nurses, reported feeling anxious when talking with family about death or even using the word dying.

Thus, the HCPs distanced themselves from patients at or nearing their EOL as a way of protecting themselves from becoming too involved. This was noted to be the case even with the more experienced nurses, who argued that, that, would help them to avoid burnout [6]. Self-efficacy which is the nurses’ belief on their ability to promote a ‘good death’ is very critical in provision of end-of-life nursing care (EOLNC). This is because self-efficacy plays a critical role in how nurses think, feel and behave [7].

The person nearing EOL may be disregarded by family, friends, and the healthcare members as they all seek for ways to prolong life [8]. But caring for one on the verge of dying should incorporate honoring living quality while recognizing the dying person as a co-creator of the emerging now and that definition of good or bad death vary across social groups [1]. Therefore, nurses need to always remember that EOL is expected and being at ease with this view will make EOLNC a good experience that would lead to a ‘good death’.

This was also echoed by Young, Froggat and Brearley (2017) in their study that was conducted among staff working in a nursing home. They noted that good experience by the staff towards EOLC led to a ‘good death’ while bad experience led to a ‘bad death’. For instance, effective communication within the team of care at EOL was observed to lead to a ‘good death’ while poor communication led to negative experience by the staff which in turn led to a ‘bad death’.

Additionally, values for the staff within the team were also noted to affect the staff behavior [9]. That is, when the staff values within the team were congruent with each other, they believed that a patient had a ‘good death’ as the staff was able to do what was required. All in all, nurses felt unprepared to provide EOLNC. Therefore, this study intended to assess nurses’ perception on their attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care for nurses in Kenya.

Material and Methods

Study Design: Descriptive cross-sectional survey research design was used for conducting study.

Study Setting: The data were collected from eight units in an acute hospital affiliated to a teaching institution.

Study Sample: A simple random sample consisted of 191 nurses, who work in the previously mentioned settings were invited to participate in the study. Seventeen nurses declined to participate in the study. So, the final participants were 173 nurses.

Inclusion criteria: The inclusion criteria set for sample selection were as follows: Kenyan nurses working in the ICU, HDU, Oncology clinic, Accident & Emergency Department, Burns Unit, Oncology ward, Palliative Care department and Renal Unit and on full time employment.

Tool of the study: For data collection a self-administrative questionnaire was developed by researchers and used to assess: a) nurses’ socio-demographic characteristics as regards their age, professional qualification, work station, prior training in end-of-life care; and b) participants’ attitudes toward EOLNC. Attitude was assessed using a Likert scale (ranging from not at all effective 1 to very effective 3). It had seven (7) item rating with the highest score of 3 for each option and a total possible score was 21. The attitude scores were categorized into ‘not effective’ (mean ≤ 2.4) and ‘effective’ (mean ≥ 2.5).

Validity and reliability of the study: The questionnaire was revised and validated by a panel of seventeen experts in academic and clinical. The experts agreed on the items in the questionnaire. Internal consistency among the questionnaire items was 0.94 Cronbach’s alpha (α) and it was considered within the acceptable range.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the nursing department at the University of Nairobi. This was emphasized by NACOSTI agreement with their permission for the researchers to use the targeted hospital. The hospital further gave permission to the researchers to access the sample unit. Approval from nurses was obtained. Various strategies were utilized to protect the nurses’ rights who agreed to participate in the study. Consent of the nurses was obtained prior to the administration of the questionnaire. The nurses were informed of the purpose of the study, and that they had the right to decline to participate. The researcher stressed that participation was voluntary and confidentiality was observed. The nurses were informed that they can terminate at any time while the researcher ensured that anonymity of the nurses was maintained at all times.

Study limitations

Lack of a standard tool in the hospital involved was a challenge of this study to assess the real attitude of nurses on EOLNC. Lack of similar studies carried out in Kenya makes the discussion difficult. Since the units were purposively selected, it could be open to bias in case units with specific characteristics were selected.

Results

The sample unit was consisted of 173 nurses who responded to the questionnaire. The respondents’ age was as follows: 52.3% (n = 81) were aged between 31–40 years; 25.2% (n = 39) were aged between 41–50 years; 18.1% (n = 28) were in the age bracket of 20–30 years; and finally, the least in the sample unit were aged between 51–60 years. With regard to nursing qualifications: 66.9% (n = 117) of the respondents were diploma holders while 21.1% (n = 37) were undergraduate. The dominant work stations of the respondents were ICU (37.9%; n = 66) and Accident & Emergency (25.9%; n = 45). This was followed by 12.2% (n = 21) from Renal Unit; 9.8%, (n = 17) from Burns Unit; 5.2% (n = 9) from Oncology ward; 3.4% (n = 6) from HDU and oncology clinic (each). The least number of participants came from palliative care unit (2.3%; n = 4). Regarding training in end-of-life care, none of the nurses had undertaken a training in end-of-life care though 11.8% (n = 20) of the nurses had received a training in palliative care.

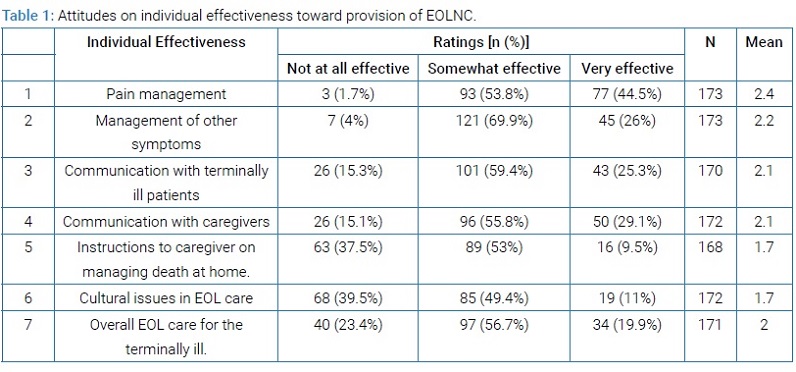

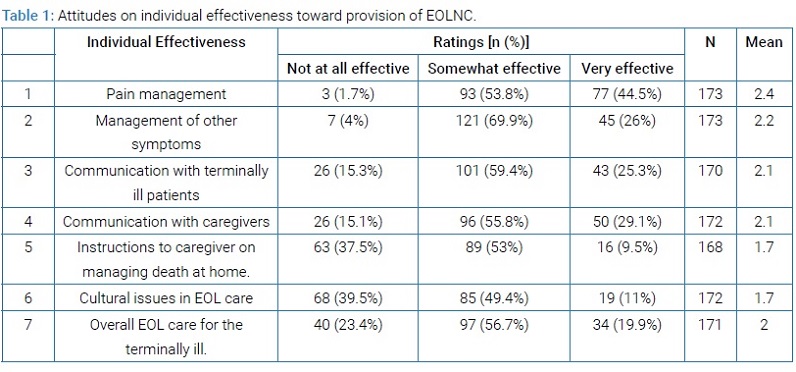

When assessed on their effectiveness as far as EOLNC was concerned, findings in (Table 1) below indicated that more than half of the nurses rated their individual effectiveness towards EOLNC to be ‘somewhat effective’ in six items out of the possible seven items assessed.

The item on cultural issues at EOL care had 39.5% (n = 68) of the respondents rating their individual effectiveness as ‘not at all effective’. Taking into consideration the mean values arrived at using Likert scale with 7 items, respondents rated their attitudes as somewhat effective (mean 2) an indication that the participants did not believe in themselves as far as provision of EOLNC was concerned.

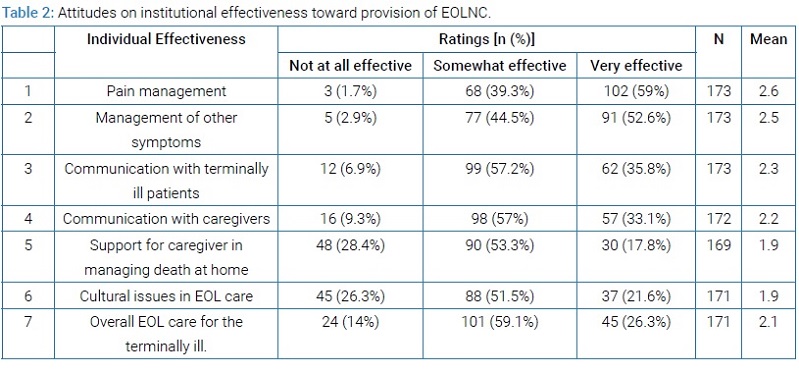

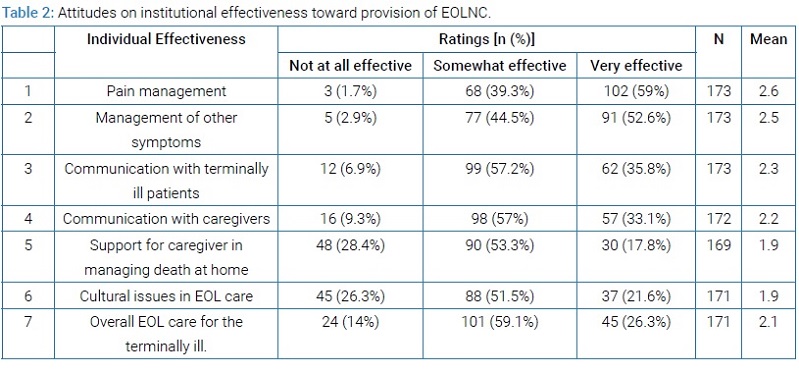

Further, the respondents were asked to rate their perception as far as the effectiveness of their institution was concerned in provision of EOLNC and they had the following sentiments: more than half of the respondents indicated that their institution was very effective as far as pain management and management of other symptoms at EOL was concerned. However, more than half of the respondents rated their institution to be somewhat effective on six items assessed pertaining to: communication with terminally ill patients; communication with family caregivers; support for family/caregiver in managing the death event at home; cultural issues in EOL care; and overall EOL care for the terminally ill (Table 2).

Findings indicated that there were deficiencies especially concerning communication with the terminally ill patients and their caregivers. Therefore, taking into consideration the mean values arrived at using Likert scale with 7 items, respondents rated their belief towards institutional effectiveness as somewhat effective (mean 2) an indication that the nurses believed that there were gaps in their institution as far as provision of EOLNC was concerned.

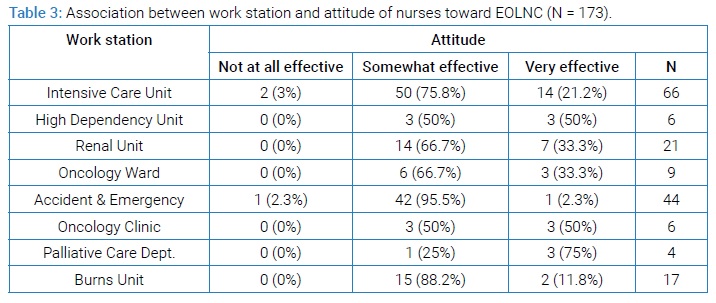

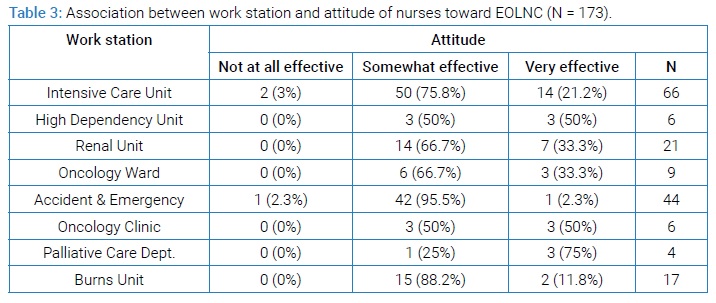

Regarding the relationship between work station and attitude, results showed that majority of the respondents (>60%) from five out of the eight work stations investigated agreed that their attitudes were somewhat effective (Table 3).

One work station had a majority of the respondents rating their effectiveness towards EOLNC as very effective, the palliative care department (75%; n = 3). Notably, two other work stations had half of the respondents indicating that their effectiveness towards EOLNC was very effective; namely, HDU (50%, n = 3) and oncology clinic (50%, n = 3) (Table 3). Therefore, majority of the respondents (75%) felt that they had deficiencies in their EOLNC attitudes as was indicated by the high rating in the somewhat effective responses. Thus, the results indicated that some differences existed between the work station and nurses’ perception on their attitudes toward EOLNC as nurses from three out of the eight work stations rated their attitudes toward EOLNC as very effective while the rest rated as somewhat effective. However, the difference that existed in the rating of EOLNC as tabulated in (Table 3) was not assessed for statistical significance as this was not the objective of the study.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that the Kenyan nurses perceived their attitudes to be somewhat effective toward provision of end-of-life nursing care (EOLNC), an indication that the nurses possessed negative attitudes toward end-of-life care. This finding is consistent with the study done in Ethiopia in which more than half of the respondents had negative attitudes toward EOLC [10]. Additionally, in a study on nurses’ perceived self-confidence in provision of EOL care, Coffey, et al. [11] observed that nurses did not consider themselves to be effective in provision of EOL care. Moreover, low perception by nurses regarding their self-perceived EOL care competencies was also noted in one other study by Montagnini and colleagues [12].

From the same study, it was noted that the nurses scored their confidence much lower than their counterparts in the medical field. Lack of confidence by nurses towards provision of EOL care could be linked to the fact that the nursing profession has for decades been considered an aide to the doctor and thus all the nurse was expected to do was to carry out orders. This position may have affected the perception that nurses have towards themselves. Additionally, another possible explanation for this result may be because nurses are uncomfortable talking about death thus developing a negative attitude towards a topic that makes them uncomfortable. This is more so, an avoidance technique to a situation that nurses perceive as stressful. Use of avoidance technique by nurses to a stressful situation is documented in literature [13].

Findings from this study also indicated that the nurses did not have confidence in the effectiveness of their institution as far as provision of end-of-life care was concerned. This observation is consistent with that reported in a study that was conducted in England on end-of-life care pathways within acute hospitals. Findings from that study indicated that there were numerous challenges that nurses faced while providing end-of-life care within an acute hospital [14]. The lack of confidence by nurses in this study could have resulted from lack of protocols pertaining to end-of-life care within the hospital as this is an area that receives low priority in care provision. That notwithstanding, nurses from three out of the eight work stations rated their attitudes toward EOLNC as very effective. This was an indication that nurses from these units possessed positive attitudes toward EOLNC.

The importance of positive attitudes by nurses in provision of EOLNC is key, not only for the quality of EOLNC provided but also for better health of the nurse [15]. This was highlighted in a study conducted among nurses working in neonatal intensive care unit as it was reported that majority of the nurses had positive attitudes toward EOLC [16]. Similar sentiments were reported in a study conducted in Japan in which a positive attitude towards providing EOLC was noted to decrease burnout [17].

The benefits of positive attitude recorded by Okamura and colleagues [17] emphasizes the importance of supporting nurses providing EOLC by improving their attitudes. This is so especially at a time when the nurses in Kenya are faced with the increasing number of deaths in the hospital due to an increase in the aging population as well as an increase in deaths due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [18]. Overall, there were differences pertaining to nurses’ attitudes towards EOLNC with some of the nurses reporting negative attitudes and with a few reporting positive attitudes. This difference might be because of cultural differences related to talking about death in front of the patient and or their family. Moreover, breaking bad news also has cultural variations. The differences could also be explained by the nurses’ values and religious beliefs which may affect their belief towards provision of EOLC.

Furthermore, the positive attitudes reported in this study by some of the nurses could be attributed to the fact that these nurses had improved their attitudes from their experience of nursing patients with chronic illness. This is so because the said nurses worked in either palliative care unit, high dependence unit or oncology clinic and this may have exposed them to caring for patients with life threatening illness. The importance of experiential learning is well documented in literature. For example, in a study by Barrere and Durkin [19] on new nurses experiences on EOLC, nurses reported that EOLC could be better understood through experiencing it.

In conclusion, findings of this study showed that most of the nurses had negative attitudes toward end-of-life care. This suggests the need for training in end-of-life care because nurses’ attitudes toward caring for dying patients may influence their behavior as well as the quality of care that they provide. Additionally, there is need for mentorship and modelling of nurses within the health facility as nursing experience on EOLC may positively influence nurses’ attitudes, further highlighting the need for a critical mass trained in EOLNC. Lastly, the need for in-service training programs cannot be overemphasized.

Conclusion

Nurses had deficiencies in their attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care (EOLNC) which may be attributed to lack of education on end-of-life nursing care. This study therefore, highlights the need for development of EOLNC educational programmes to facilitate nurses’ understanding of their attitudes toward EOLNC as they strive to improve the quality of EOLNC. This can be done through formal or informal education in both academic and hospital settings. Hence, it is important that nursing schools incorporate courses related to end-of-life nursing care so as to improve their students’ attitudes while continuing education courses on end-of-life nursing care will foster an attitude of caring and compassion. This is especially so because attitudes are learned.

Implications for Practice

This is the first report from Kenya on nurses’ attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care. It is hoped that this study offers insight into the need for development of educational programmes that will help nurses to understand their attitudes toward end-of-life nursing care. These educational programmes should be tailored to address the specific unit needs according to patient acuity level.

Acknowledgement

The researchers are grateful to the nurses in the targeted government hospital for their participation in this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Cain CL, McCleskey S. Expanded definitions of the “good death”? Race, ethnicity, and medical aid in dying. Sociology of health & illness. 2019;41(6):1175–1191. doi:10.1111/1467–9566.12903.

- Chan HYL, Lee DTF, Woo J. Diagnosing Gaps in the Development of Palliative and End-of-Life Care: A Qualitative Exploratory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 [accessed 2020 Mar 20];17(1). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6982034/. doi:10.3390/ijerph17010151.

- Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, Fukutaki K, Fullman N, McGaughey M, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. The Lancet. 2018;392(10159):2052–2090. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31694–5.

- Nedjat-Haiem FR, Carrion IV, Gonzalez K, Ell K. Exploring Health Care Providers’ Views About Initiating End-of-Life Care Communication. The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2017;34(4):308.

- AlFayyad IN, Al-Tannir MA, AlEssa WA, Heena HM. Physicians and nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards advance directives for cancer patients in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0213938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213938.

- McConnell T, Scott D, Porter S. Healthcare Staff’s experience in providing end-of-life care to children: A mixed-method review. Palliative Medicine, 2016;905–919.

- Abate AT, Amdie FZ, Bayu NH, Gebeyehu D, G/Mariam T. Knowledge, attitude and associated factors towards end of life care among nurses’ working in Amhara Referral Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Research Notes. 2019 [accessed 2020 Mar 20];12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6700991/. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4567–7.

- Finucane AM, Bone AE, Evans CJ, Gomes B, Meade R, Higginson IJ, et al. The impact of population ageing on end-of-life care in Scotland: projections of place of death and recommendations for future service provision. BMC Palliative Care. 2019 [accessed 2020 Mar 20];18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6907353/. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0490-x.

- Young, Amanda, Froggat, Katherine, Brearle, Sarah G. ‘Powerlessness’ or ‘doing the right thing’ – Moral distress among nursing home staff caring for residents at the end of life: An interpretive descriptive study. [accessed 2020 Apr 1]. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/31045.

- Abate AT, Amdie FZ, Bayu NH, Gebeyehu D. Knowledge, attitude and associated factors towards end of life care among nurses’ working in Amhara Referral Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC research notes. 2019;12(1):521.

- Coffey A, McCarthy G, Weathers E, Friedman MI, Gallo K, Ehrenfeld M, et al. Nurses’ knowledge of advance directives and perceived confidence in end‐of‐life care: a cross‐sectional study in five countries. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2016;22(3):247–257. doi:10.1111/ijn.12417.

- Montagnini M, Smith H, Balistrieri T. Assessment of Self-Perceived End-of-Life Care Competencies of Intensive Care Unit Providers. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012;15(1):29–36. doi:10.1089/jpm.2011.0265.

- Price DM, Strodtman L, Montagnini M, Smith HM, Miller J, Zybert J, et al. Palliative and End-of-Life Care Education Needs of Nurses Across Inpatient Care Settings. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2017;48(7):329–336. doi:10.3928/00220124-20170616–10.

- Hewison A, Lord L, Bailey C. “It’s been quite a challenge”: Redesigning end-of-life care in acute hospitals. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2015;13(03):609–618. doi:10.1017/S1478951514000170.

- Hu Y, Jiao M, Li F. Effectiveness of spiritual care training to enhance spiritual health and spiritual care competency among oncology nurses. BMC Palliative Care. 2019 [accessed 2020 Mar 20];18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6880564/. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0489-3.

- Park JY, Oh J. Influence of Perceptions of Death, End-of-Life Care Stress, and Emotional Intelligence on Attitudes towards End-of-Life Care among Nurses in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Child Health Nursing Research. 2019;25(1):38–47. doi:10.4094/chnr.2019.25.1.38.

- Okamura T, Shimmei M, Takase A, Toishiba S. A positive attitude towards provision of end-of-life care may protect against burnout: Burnout and religion in a super-aging society. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202277. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0202277.

- World Health Organization - Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles, 2018. https://www.who.int/nmh/countries/ken_en.pdf?ua=1.

- Barrere C, Durkin A. Finding the Right Words: The Experience of New Nurses after ELNEC Education Integration into a BSN Curriculum. MEDSURG Nursing. 2014;23(1):35–53.

Keywords

Cronbach’s alpha; End-of-life care; Nursing care

Cite this article

Machira G, Mageto IG, Mwaura J. Self-perceived attitudes toward end-of-life care among nurses working in acute hospital in Kenya. Clin Oncol J. 2020;1(1):1–6.

Copyright

© 2020 Gladys Machira. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY-4.0).